Deborah J. Cooper

FAIA, LEED AP BD+C

Principal

In 2005, I was invited to contribute to an exhibit at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, “Scents of Purpose: Artists Interpret the Spice Box.” The spice box is passed around during the havdalah ceremony, which marks the conclusion of Shabbat, so everyone can smell the sweet fragrance as a sendoff into the coming week. The exhibit was part of a series that the museum sponsored, commissioning artists to create original interpretations of traditional Jewish ritual objects. I, along with the architects from WRNS and Daniel Libeskind’s office, who were all working on the design of the new Contemporary Jewish Museum at the time, were asked to contribute to the show. It was a fun challenge for all of the architects to create these objects.

Neriage technique

I had an idea of what I wanted to make but had to figure out how to do it. I’d been taking glass-casting classes, but knew I didn’t have the skills to execute my vision in glass. So I found a ceramics studio and asked the teacher, Saadi Shapiro, to help me realize an idea I had, which was to make the spice boxes in the shape of different fruits.

That experience launched me into making ceramics. That and the fact that, after joining ARG and completing the design of Cavallo Point: the Lodge at the Golden Gate, I accumulated so much overtime that I had to start taking Fridays off every week. I would go to the ceramic studio at Merritt College and work with Saadi—I call him my ceramic angel. He gave me three pottery wheels and a kiln, so I now have a studio in my basement!

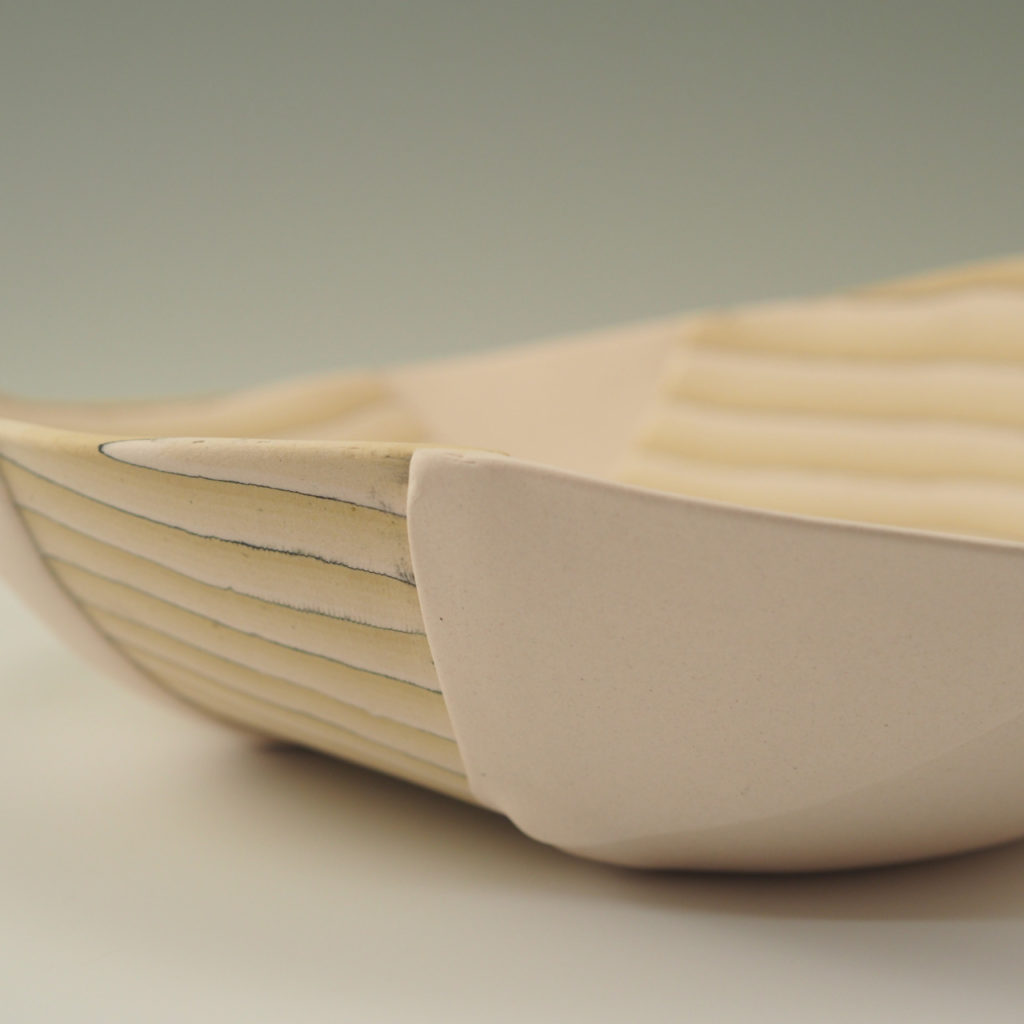

Nerikomi technique

I discovered neriage and nerikomi while visiting a pottery in Calistoga. These are two ancient Japanese techniques that allow you to create patterns with colored clay that are similar to the Italian millefiori technique. With neriage, you combine different colors of clay in a ball, then throw it on the potter’s wheel. The spinning of the wheel creates the pattern. With nerikomi, you stack or roll up the layers, slice them to see the cross-sections—it’s kind of like making sushi—and then hand-mold the slices into their final forms. The resulting pieces have intricate patterns. I started playing around with those techniques to make works of porcelain.

I really got inspired when I discovered the website of Dorothy Feibleman’s translucent nerikomi expression. It turned out she was teaching a workshop at the International Ceramics Center in Kecskemét, Hungary, a couple hours south of Budapest. I decided to go, even though it was only a couple of months away.

Slip inlay technique

After a weekend in Budapest, I went to Kecskemét for a week of learning from Dorothy. There were about 15 of us. We’d go into the studio in the morning for two-hour-long demonstrations, and then we’d have a little time to work on our own. In the afternoon, she’d give another two-hour demonstration, teaching us her techniques. Then we’d spend the night working.

It was so much fun. There were people from all over. There was a woman from Slovakia, a woman from Israel, and a number of Hungarians, all there to learn from a master. One guy was an American who lived in Indonesia—he made highly intricate guitar bodies out of polymer clay, but using a similar technique.

Now that I’m a principal, I confess it’s hard to squeeze ceramics into my life. But I still find time to get into the studio once in a while.

People often ask me if I sell my pieces. But for me, it’s really not about selling the work. It’s about exercising my creativity. And it’s an activity that balances architecture well—and not just because it’s so hands on. With ceramics, you can finish a piece in a few months. Try pulling that off with a lodge or a museum.