In the opening scene of the 1960 film Spartacus, the eponymous hero (played by Kirk Douglas), fighting to protect a fellow slave, bites the ankle of a Roman guard. The melee unfolds high on a ridge in a stunning desert landscape, played by an actual mining camp: Ryan Camp in Death Valley, California. In an effort to restore and maintain the site, we’re applying modern technology—3D documentation and building information modeling—to this 103-year-old complex. This new technology provides us with a way to comprehensively document the camp’s assets, create a 3D building management tool, and ultimately keep restoration costs down.

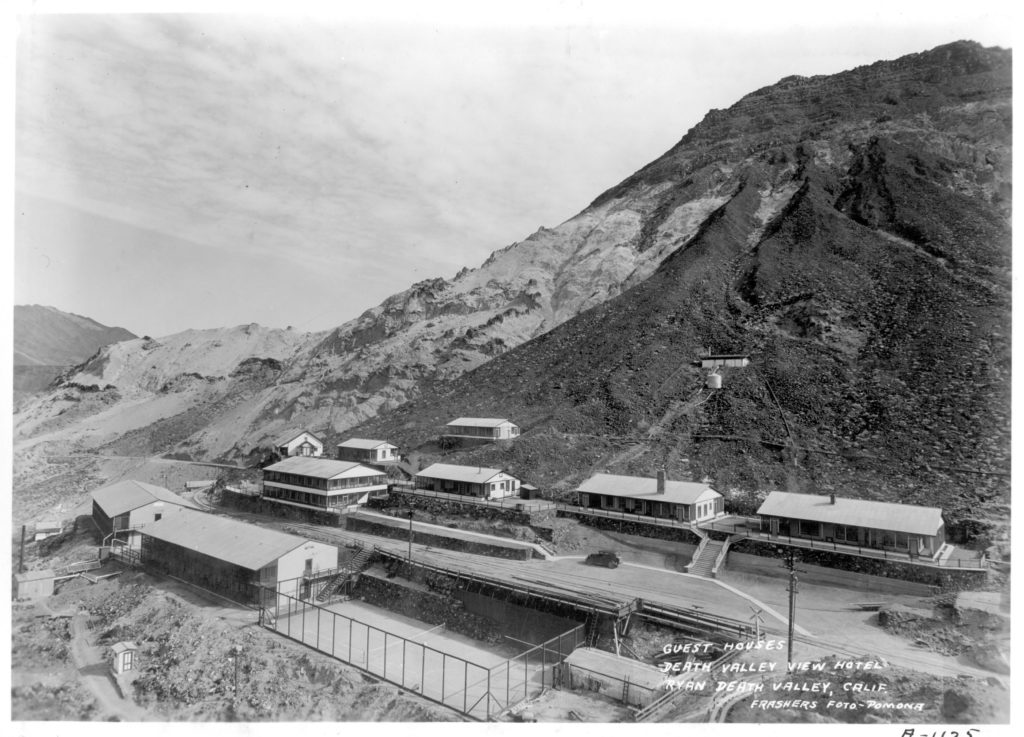

A little history first: Death Valley may have a reputation today as one of the world’s hottest places, but in the late 19th century, it was also known as a rich repository of borate, a chemical compound with a wide variety of industrial uses. The Pacific Coast Borax Company set up the Ryan mining camp in 1914, eventually expanding it to include a school, a hospital, a post office, a recreation hall (in a former church building moved from Rhyolite, Nevada), and a general store. After moving operations elsewhere in the late 1920s, the company reworked the camp to serve as a base for tourism, creating the “Death Valley View Hotel”—a tempting name for a hotel if there ever was one.

Historic image of the Death Valley View Hotel taken in 1930

In 2013, the Pacific Coast Borax Company’s successor, Rio Tinto, donated the camp to the Death Valley Conservancy, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving, protecting, and enhancing Death Valley National Park. Many buildings are still standing—simple, wood-frame structures, about 15 in all: two worker dormitories, four staff houses, a lobby/dining room/kitchen complex, the school, the church/recreation hall, a hospital, a warehouse, a boiler house, and a powerhouse. The Death Valley Conservancy brought us in to help with its efforts in restoring the camp so it can continue to support education and research as well as host occasional visitors. The camp isn’t open to the general public, aside from small public tours several times a year.

An overall photo of the historic Ryan town site today.

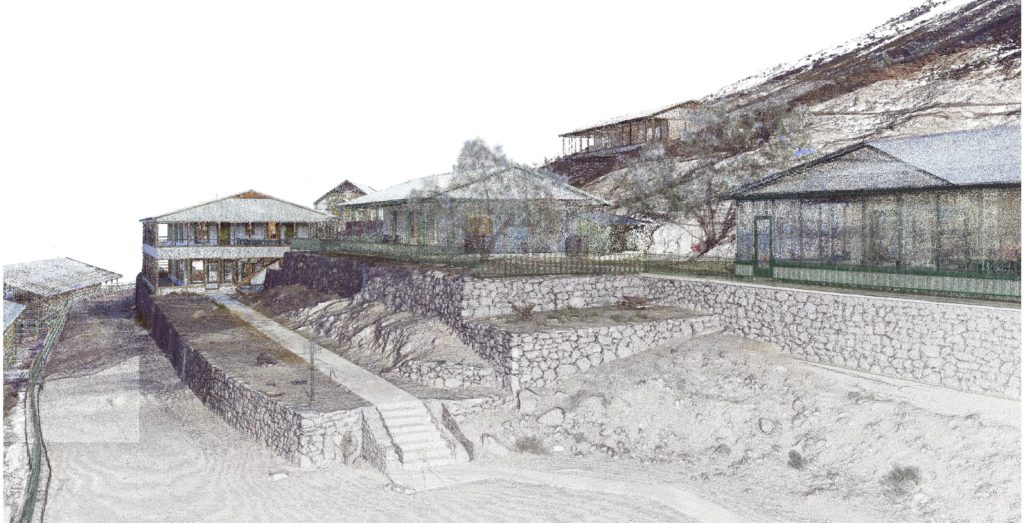

To provide a foundation for the restoration, ARG and the Death Valley Conservancy brought in Epic Scan, a company that specializes in the 3D documentation of existing conditions, to help us create an incredibly rich, detailed representation of the camp using laser scanning and photogrammetry technology. It was one of the largest 3D documentation jobs Epic Scan has undertaken, with the terrestrial documentation of nearly 40 acres of land and buildings.

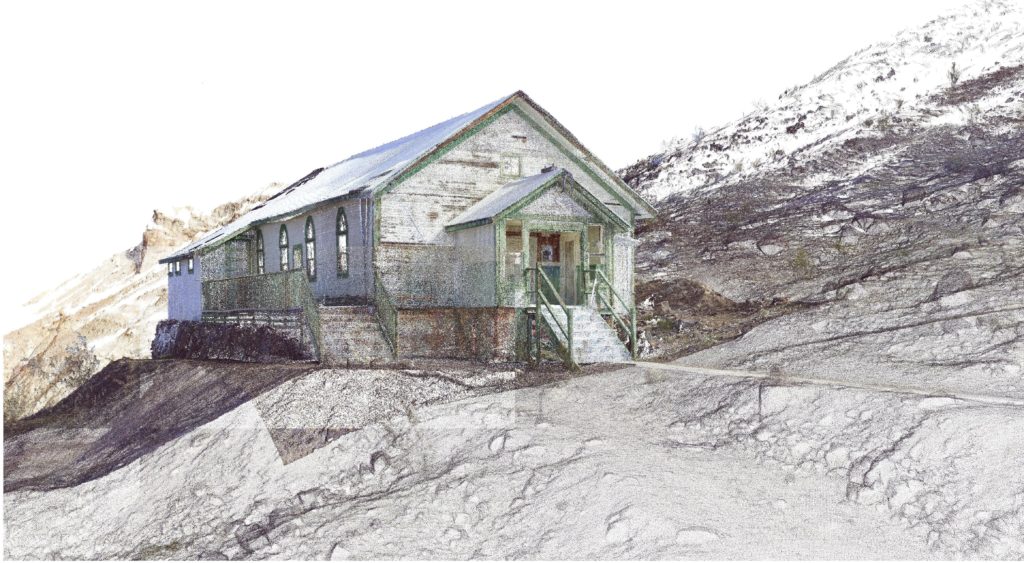

Ryan was the perfect candidate for 3D documentation for several reasons. First, due to the remote location, 3D documentation allowed us to capture an extremely accurate record of the site at one time, preventing us from having to make multiple costly, long-distance trips back to Death Valley for later documentation. Secondly, we were interested in documenting not only the buildings, but also the complex and unique topography associated with them—the camp is located on a steeply sloping mountainside. With 3D documentation, we were able to capture both of these aspects at one time. Lastly, the site is rich in building vestiges and archaeological features like a skip track, a dump trestle, and even remnants of the Spartacus film set. By using laser scanning, we were able to efficiently document these resources so that we have an accurate 3D representation of them and their locations in case any natural occurrence were to threaten their existence.

A view of the 3-dimensional point cloud data captured at Ryan, CA.

There were two different 3D documentation technologies used in order to capture the extent of the almost 40-acre site. Terrestrial laser scanning was used to document all of the buildings, mining structures, and archeological features at a high resolution. With this form of documentation, a laser scanner sits on a tripod and collects 360 degrees of information at one time. Every time the scanner’s laser hits an object, it receives information about how far away that object is and registers it as one single point. A laser scanner can capture nearly 1 million individual points per second. Epic Scan supplemented the 3D documentation effort with aerial photogrammetry, sending a drone over the mountains to collect data from above. The drone collected thousands of photographs of the site from numerous vantage points, capturing in total 400 acres of data. This photographic data can then be used by special software to create a 3D point cloud model. The point clouds from the two different methods, terrestrial laser scanning and aerial photogrammetry, were then merged together into one large comprehensive 3D representation of the entire site.

A view of the Ryan Rec Hall building 3-dimensional point cloud data.

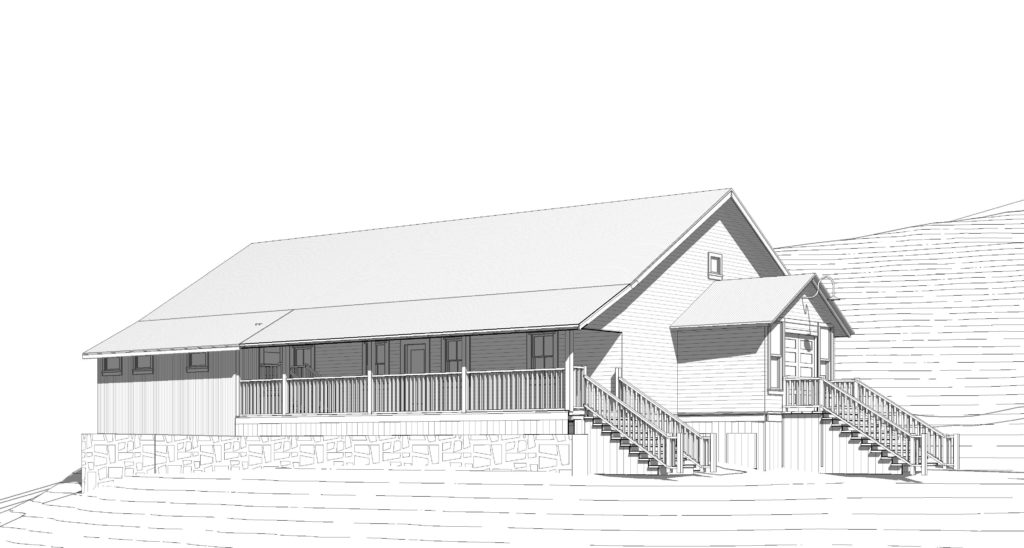

ARG took the data collected from the 3D documentation and turned it into a building information model, a 3D model that allows the user to add information to the various elements within the model. For instance, when we draw a wall, door, or window, we can tag those individual three-dimensional elements with information such as the material, size, type, and location. In addition to incorporating this basic information, our goal for the Ryan Camp project is to continue adding other layers of information to the model, such as historical data: when things were constructed, who constructed them, and possibly whether or not elements were altered.

A view of the Ryan Rec Hall BIM model that was created by use of the 3-dimensional point cloud data.

The building information model will help the Death Valley Conservancy to better understand, organize, and manage its property and assets, giving concrete form to institutional memory. The areas of the site in which we have added the most amount of detail and information are the recreation hall and an exterior stairway on one of the bunkhouses; these areas are first in line for restoration. As we move forward, information added to our building information model will include details concerning any new work we are doing at the site, ensuring an accurate record of Ryan’s ongoing evolution.

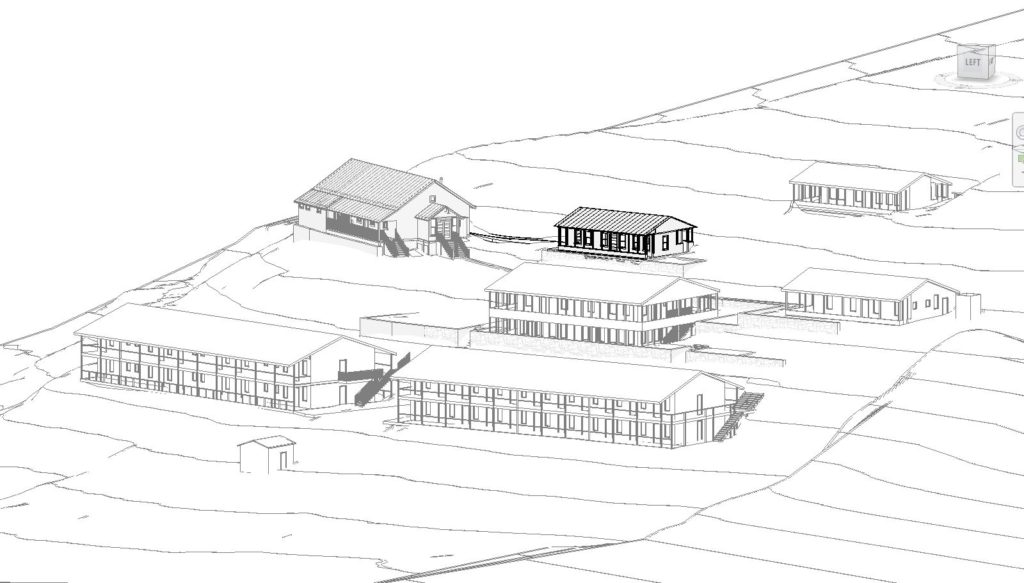

An overall view of the Ryan BIM Database, showing several of the Ryan buildings.

Relying on 3D documentation for historic preservation projects does require a fairly substantial upfront cost, but it can also save a lot of money down the road. Many historic buildings have complex and/or detailed building elements that can be very difficult and time consuming to document using traditional methods. Therefore, traditional hand measuring documentation techniques may result in surprises during construction due to inaccurate as-built documentation. When this is the case, a lot of money gets spent later in the project on change orders due to errors resulting from inaccuracies in the initial documentation. With laser scanning, we can be much more confident that we know what the existing conditions are, thus resulting in fewer costly change orders down the road. We’ve used laser scanning on a number of our projects, including the Cooper Molera Adobe in Monterey and the Hop Kiln Winery in Healdsburg.

Our use of 3D documentation at Ryan is already helping complex restoration projects run more smoothly, as well as preserving valuable historic information. From mining camp to hotel to film location, Ryan has had an extraordinary past—we are very excited to see what its future holds.