Kitty Vieth

AIA, LEED AP

Principal

In the years following World War II, the U.S. national parks experienced a popularity problem. With the rise of auto tourism, the annual number of visitors to national parks shot up from 11.7 million in 1945 to 61.6 million in 1956. At Yosemite National Park alone, annual visitors surpassed the one million mark during that period. The old, small, Rustic-style visitor facilities couldn’t handle the crowds. Something had to change.

A copy of the Mission 66 brochure published by the National Park Service in 1960 and found at the Yosemite Research Library

To address this, in 1956, the National Park Service (NPS) launched Mission 66, a program of new infrastructure and building. The goal was to finish the program in 10 years, in time for the park service’s half-centennial in 1966.

With the program came a new approach to architecture that drew on the modernist tenets of the day. Out with the old Rustic style: timber, shingles, shakes, and stone—the picturesque “log cabin in the wilderness” aesthetic. In with the new: contemporary forms and modern materials, such as concrete and steel, with expanses of glass to put the emphasis on the view. The new buildings had to be much larger than their predecessors to accommodate the new high level of usage, so modernism’s low-slung forms with minimal ornamentation and modern construction efficiencies made sense.

Although the style change caused some consternation at the time by fans of the old aesthetic, the facilities from the Mission 66 era are now historic themselves. That requires a shift in thinking and a plan for rehabilitation.

Indoor/outdoor dining area at Yosemite Lodge c.1960 (Yosemite National Park Archives, YP&CC Collection)

At Yosemite National Park, the NPS recently awarded a 15-year contract to a new concessioner, Aramark, to operate the park’s hospitality programs and facilities. Aramark proposed a number of rehabilitation projects and a schedule to complete them. Before they could proceed, however, the NPS needed to understand the structures as historic resources. Most of the Mission 66–era buildings in Yosemite hadn’t been documented in any way, and the Yosemite Valley Historic District only includes buildings built before 1942.

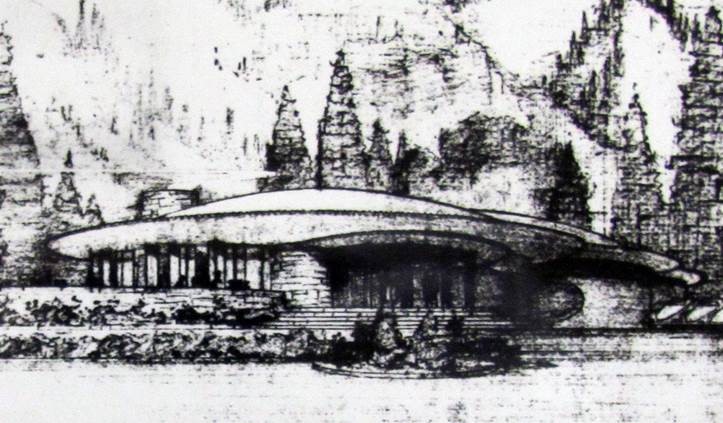

So the NPS asked us to start developing historic structure reports (HSRs) for these buildings. The most significant of the group that we’ve looked at is the Degnan’s Restaurant and Loft building. It was built by the Degnan family, who had operated a bakery in the valley since the 1890s. The family decided to replace its previous facility, which was rustic, with something modern. In fact, they originally asked Frank Lloyd Wright to design it. He drew a sketch of his idea, but it proved a little bit too modern even for the NPS. The family ultimately chose Walter Wagner & Partners, an architecture and engineering firm with offices in Fresno and Merced, California. Wagner designed a strikingly modern structure, completed in 1958.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s conceptual sketch for Degnan’s Restaurant (Yosemite National Park Research Library)

As soon as we visited the building, we could immediately see a lot of what was historic and most significant about the building. It’s a very strong A frame, with a partially exposed structure. A full-height glass wall at the southeast end of the building provides unimpeded views of the landscape, and a similar glass wall at the second floor level of the northwest end frames a view of Yosemite Falls. The dramatic central concrete fireplace on the second floor has a chimney that rises up through a skylight in the ceiling. In the process of creating our report, we were able to confirm that there was another original fireplace on the first floor that had been boxed in 30 years ago. As part of recent renovations at Degnan’s, this fireplace has been exposed to view once again. (We were not involved in the design of the Degnan’s project, but our HSR was developed to serve as a guide for the work.)

Degnan’s Restaurant and Loft soon after construction was completed, designed by Walter Wagner & Partners (Yosemite National Park Research Library Negative Files, photographer: Jack E. Boucher)

Currently, we are preparing historic structures reports for two other Mission 66 buildings in Yosemite. One of them is the Village Store, which is not nearly as dramatic as Degnan’s. You might drive right by it and not give it a second glance. But when it opened in 1959, the New York Times ran an article mentioning that it “replaces an unsightly old store, which with a former maintenance structure had marred a superb view of Yosemite Falls.”

Village Store soon after construction was completed, c.1960 (Yosemite National Park Archives, YP&CC Collection, photographer: Philip Hyde)

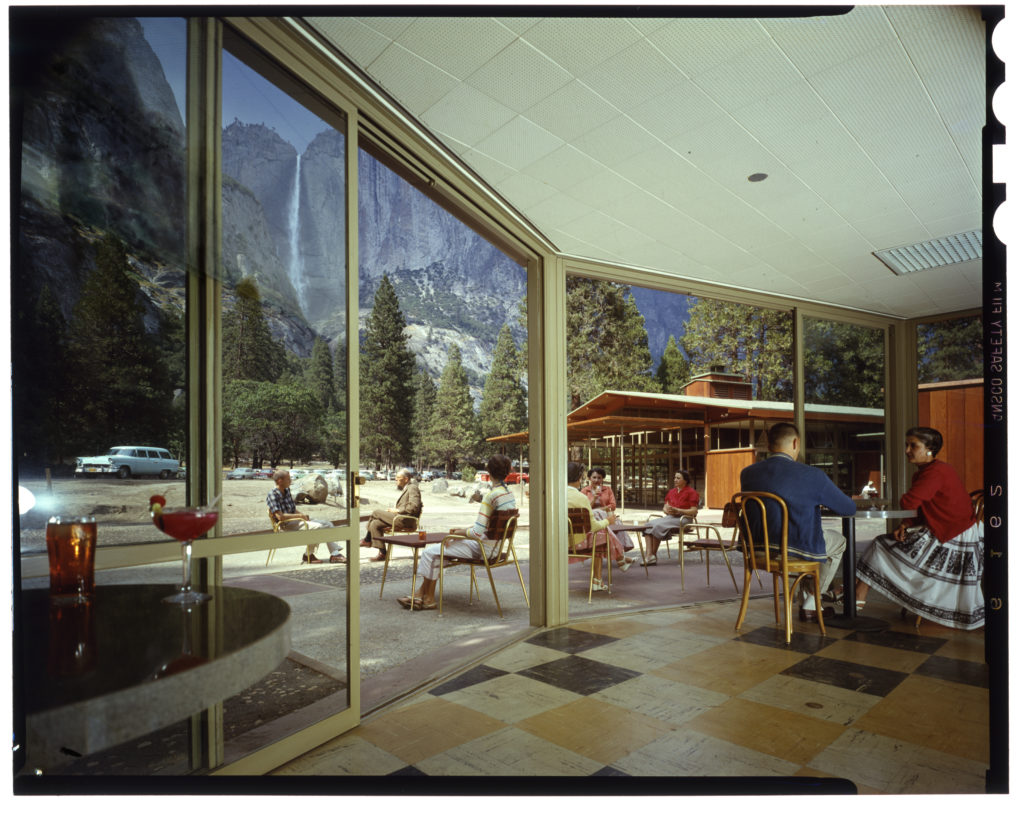

We are also working on the Food Service Building at the Yosemite Lodge. The Yosemite Lodge complex has a wonderful midcentury aesthetic. Completed in 1956, it was designed by Bay Area architect, Eldridge (Ted) Spencer, who was the architect for many years for the Yosemite Park & Curry Company, the most prominent concessioner at Yosemite. The Yosemite Lodge was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 2015.

Yosemite Lodge Grill Restaurant c.1960 (Yosemite National Park Archives, YP&CC Collection)

We found the original construction documents for the food service building, which helped our efforts a good deal. It has huge sliding steel doors that open up the food court and restaurant areas to the outdoors. The concessioner is currently rehabilitating the restaurant and cafeteria to create a more modern facility.

Yosemite Lodge Food Service Building (left) and Lounge (right) c.1960 (Yosemite National Park Archives, YP&CC Collection)

Now ARG is pleased to be in the process of evaluating all of the Mission 66 buildings and landscapes throughout the park so that planning for these features can be accomplished in a comprehensive way.

The number of annual visitors to Yosemite has surpassed 5 million, and the Mission 66 buildings are reaching their own half-centennial of use. Fortunately, they still have the capacity to meet the park’s needs while retaining and restoring historic features that make them part of visitors’ treasured memories. Though they were controversial at the time, it’s hard to imagine the park without them now.